Protected Areas

or other effective means, to achieve the long term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and

cultural values.” – International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2008)

Contents

- What is a "protected area"?

- Protected Area Benefits

- Challenges

- Protected Area Categories

- Conservation Areas in Ontario

- Websites About Protected Areas

- References

What is a "protected area"?

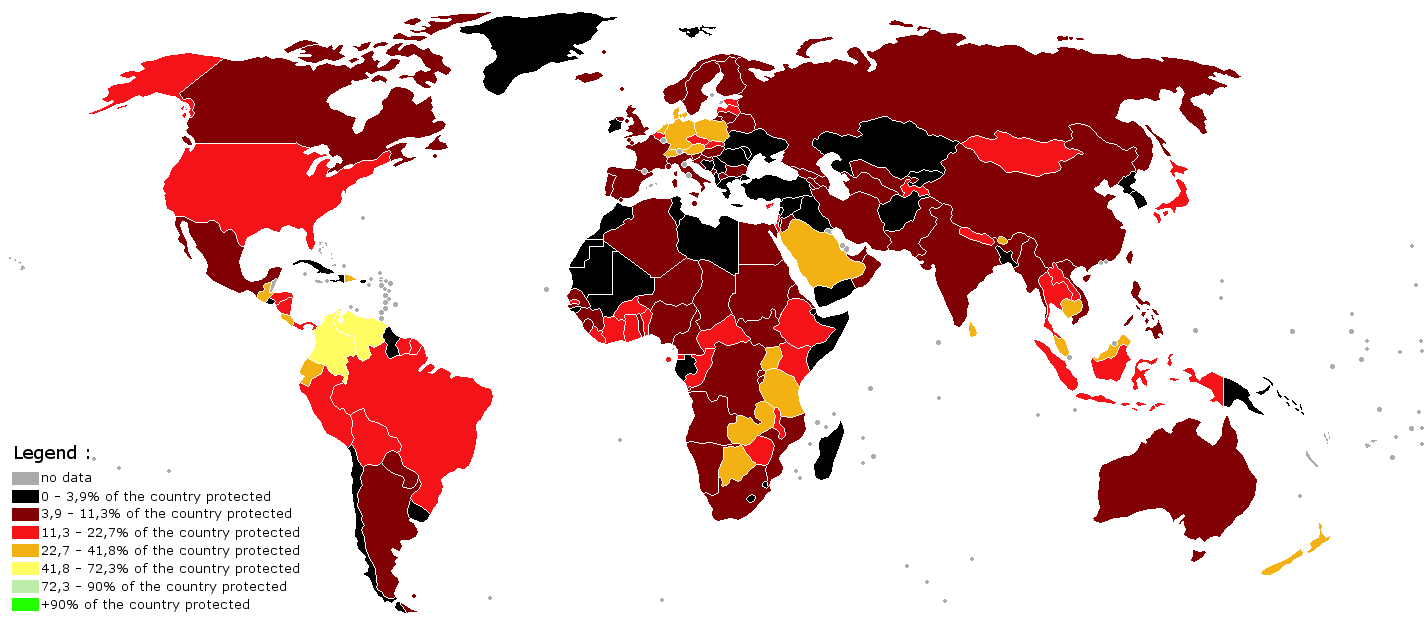

Protected areas – national parks, wilderness areas, community conserved areas, nature reserves and so on – are a mainstay of biodiversity conservation, while also contributing to people’s livelihoods, particularly at the local level. Protected areas are at the core of efforts towards conserving nature and the services it provides us – food, clean water supply, medicines and protection from the impacts of natural disasters. Their role in helping mitigate and adapt to climate change is also increasingly recognized; it has been estimated that the global network of protected areas stores at least 15% of terrestrial carbon. Global map of PAsPhoto: IUCN and WCMCHelping countries and communities designate and manage systems of protected areas on land and in the oceans, is one of IUCN’s main areas of expertise. Together with species conservation, this has been a key focus of attention of IUCN’s work and of a vast majority of IUCN Member organizations. Effectively managed systems of protected areas have been recognized as critical instruments in achieving the objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Sustainable Development Goals

Protected areas or conservation areas are locations which receive protection because of their recognized natural, ecological or cultural values. There are several kinds of protected areas, which vary by level of protection depending on the enabling laws of each country or the regulations of the international organizations involved.

The term "protected area" also includes Marine Protected Areas, the boundaries of which will include some area of ocean, and Transboundary Protected Areas that overlap multiple countries which remove the borders inside the area for conservation and economic purposes. There are over 161,000 protected areas in the world (as of October 2010) with more added daily, representing between 10 and 15 percent of the world's land surface area. By contrast, only 1.17% of the world's oceans is included in the world's ~6,800 Marine Protected Areas.

Protected areas are essential for biodiversity conservation, often providing habitat and protection from hunting for threatened and endangered species. Protection helps maintain ecological processes that cannot survive in most intensely managed landscapes and seascapes.

Protected Area Benefits: Maintaining Our Life-Support Systems

Protected areas provide a wide range social, environmental and economic benefits to people and communities worldwide. They are a tried and tested approach that has been applied for centuries to conserving nature and associated cultural resources by local communities, indigenous peoples, governments and other organisations.

More than instruments for conserving nature, protected areas are vital to respond to some of today’s most pressing challenges, including food and water security, human health and well-being, disaster risk reduction and climate change.

As the world continues to develop at a rapid pace, pressure on ecosystems and natural resources intensify. Protected areas, when governed and managed appropriately and embedded in development strategies, can provide nature-based solutions to this pressure, and take their place as an integral component of sustainable development.

- Supporting services - At a time when many agricultural systems are becoming increasingly reliant on inputs of fertilisers, pesticides and large amounts of fossil fuel energy, natural ecosystems that are self-regulating and powered solely by the sun are more rare. ‘Supporting processes and functions’ refer to the basic running of an ecosystem: soil formation and nutrient cycling; life-cycle maintenance for species by provision of services like fish nursery habitats, means of seed dispersal and continued species interactions; along with conservation of the full range of biodiversity. By protecting functioning ecosystems, protected areas provide services to surrounding ecosystems, both through the direct spillover of soils, nutrients and intercepted solar energy and from the potential to use protected areas as baselines of information and raw materials for restoration within the rest of the landscape. For example, demonstration of the opportunities for land restoration through dryland habitat protection amasses important information, and builds confidence, for authorities to tackle desertification issues in the Arabian Peninsula. Reductions of desertification and dust storms are two concrete results that can become apparent in a small number of years; however, major challenges here are that a generation or more of people have grown up believing that the highly degraded ecosystems covering most settled parts of the peninsula are ‘natural’. Policy changes rely not only on proof that protection and restoration can work, but also on a long-term effort to build understanding about ecology in the countries concerned.

- Provisioning services - Of more immediate interest to people are the various

tangible resources that protected areas either provide

directly or support.

- Food

Well-managed natural ecosystems play a key role in food security, particularly for the poorest members of society, many of whom are still leading a subsistence lifestyle and are dependent on a diversity of edible products from protected areas. For example, freshwater and marine protected areas and coastal mangroves provide valuable breeding grounds for fish, ensuring the populations do not collapse and providing spillover into surrounding waters (Roberts and Hawkins 2000). Many marine protected areas also allow sustainable fishing for local communities, or follow traditional seasonal closures. Terrestrial protected areas also enhance food security, by such measures as providing emergency grazing during times of drought in drylands, sources of fodder as long as this is harvested in a sustainable manner and even allowing controlled extraction of food species from within the protected area boundaries. Illegal overhunting within protected areas is conversely a major problem. The use of protected areas as ‘emergency’ food supplies is highlighted, for instance, in some parts of northern and eastern Africa (Dudley et al. 2008). - Water

Some ecosystems also increase the net amount of available water, particularly watersheds containing cloud forests, where leaves ‘scavenge’ water from mist and cloud, condensing it on specially evolved leaf parts and then funnelling it down branches and trunks. The city of Tegucigalpa in Honduras is one of several large Latin American cities that protect surrounding cloud forest to guarantee water supplies, in this case in the La Tigra National Park (Hamilton 2008). In some ecosystems forests can hold more rainfall in the catchment than cleared land, reducing water export and (depending on geology) increasing aquifer storage (Siriwardena et al. 2006). - Raw materials

Many protected areas have been established explicitly to conserve natural resources such as timber and valuable plants. But an increasing number also sanction some level of collection, usually by local communities and focusing on items like poles for building and fencing, grasses for thatching, firewood and more valuable timber for carving, boatbuilding and numerous other nontimber forest products (NTFPs). Some extractive reserves (IUCN Category VI) have been set up explicitly to allow sustainable harvesting of key products from natural ecosystems; here protection and production inherently go hand-in-hand. Rubber collecting in Amazonian extractive reserves is the original, classic example. The Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve in Brazil is part of a large conservation complex of more than 6 million hectares where biodiversity conservation is balanced with the needs of sustainable development. But today such approaches are being used in land and waterbased protected areas throughout the world; it is now the fastest-growing of all protected area management categories.

- Medicinal resources

Protected areas help support public health in a number of ways: by providing a sustainable source of medicinal herbs that are still the medicines of choice for the majority of the world’s poor people, and providing genetic resources for pharmaceutical companies, some of which have signed agreements to pay prospecting rights to individual protected areas. Ethno-botanical studies have been conducted in numerous protected areas, showing not only the wide range of values these places contain, but also that in many parts of the world some species, and sometimes also the knowledge on using these species, is increasingly being confined to protected areas. In countries such as Nepal, access to medicinal herbs has declined so steeply in some areas that management agreements to collect small amounts in national parks are now the only remaining option (Stolton and Dudley 2010b). - Genetic resources

As mentioned above, biodiversity has more than simply aesthetic or ethical values, but provides raw material for a range of products including the pharmaceuticals already highlighted and particularly crop wild relatives (CWR)—wild species that are closely related to domesticated crops and which can supply valuable genes for breeding to address issues such as drought tolerance or resistance to disease (Stolton et al. 2006; Hunter and Heywood 2011). Crop wild relatives already support the multi-billion-dollar annual seed business and the need for CWR is increasing all the time as environmental conditions shift rapidly under climate change, throwing agriculture under additional stress. Several microreserves have been established in Armenia, for instance, to protect important CWR in one of the global centres of crop diversity (see Boxes 6.2 and 6.6).

- Food

- Regulating services - Well-managed natural ecosystems also maintain a range of beneficial processes and functions with direct relevance to human wellbeing. These so-called regulating services refer mainly to the role of natural ecosystems in helping to control aspects of climate, hydrology and the water cycle, weather events and key natural systems that impact on agriculture, such as pollination. Our understanding of the value of these systems is increasing all the time.

- Storing and sequestering carbon

Although only recognised comparatively recently, the role of natural ecosystems in both storing and sequestering carbon, and thus reducing the rate of climate change, is now for many people a primary reason for conservation. Natural ecosystems form critical carbon stores, including vegetation such as forests, grasslands, wetlands and marine vegetation including seagrass and kelp beds, along with subsurface storage in humus-rich soils and particularly peat. Conversely, their destruction and subsequent release of carbon are factors currently leading to runaway climate change. Protected areas thus help both by preventing further losses of carbon to the atmosphere and, in healthy ecosystems, by sequestering additional carbon (Dudley et al. 2009). The UN Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC 2008) has calculated that a minimum of 15 per cent of the world’s stored carbon is already within protected areas. The opportunity to add to this through sequestration means that role of restoration in protected areas thus becomes increasingly important (Keenleyside et al. 2012). Canada is amongst the countries to have estimated the carbon storage benefits of its existing national park system. In 2000, its then 39 national parks were estimated to store 4.432 billion tonnes of carbon (Kulshreshtha et al. 2000). Carbon management is seen as an important factor in persuading governments to conserve natural ecosystems, although current compensation schemes proposed under Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) are not usually enough on their own to make up for values forgone in development. Carbon financing also expands the scope for the strategic growth of protected areas to encompass degraded or deforested land that is regrown, replanted or restored to protect ecosystems, endangered species or habitats, including corridors, which also contribute to adaptation to climate change. - Mitigation of natural hazards

Natural ecosystems also make cost-effective ways of mitigating various extreme weather events and the after effects of major earth movements; many of the former are becoming more frequent and more intense due to climate change. Natural ecosystems in protected areas can mitigate a wide range of hazards: 1) natural vegetation including particularly forests can help to control landslip due to snowfall and avalanche, hillside soil erosion or earth movement; 2) mangroves, coral reefs and sand dunes all act as barriers against storms, typhoons, sea-level rise and ocean surge following tsunamis; 3) riverside forest and protected natural floodplains help to absorb floodwaters; 4) natural vegetation in dryland and arid areas can prevent desertification, and reduce dust storms and dune movement; and 5) several intact forest ecosystems, particularly in the tropics, are far more resistant to fire than degraded or fragmented ecosystems (Stolton et al. 2008). The term mitigation needs to be defined clearly. No-one is suggesting that natural vegetation can prevent all damage from every extreme weather event, any more than can engineering solutions such as dykes, levees and firebreaks. But experience suggests that well-managed ecosystems can prevent or reduce damage from many, often most, such events and save money and lives in the process (Stolton et al. 2008). - Purification and detoxification of water,

air and soil

In an increasingly polluted world, ways of reducing the pollution load are urgently required. Natural ecosystems, if not overwhelmed, can help reduce many forms of pollution. Forests and vegetation types such as paramos in Latin America naturally produce pure water, and some freshwater plants play an active role in detoxification of certain pollutants. For example, in Florida’s cypress swamps, 98 per cent of all nitrogen and 97 per cent of all phosphorous entering the wetlands from wastewater were removed before this water entered the groundwater reservoirs (Ramsar Convention Bureau 2008). Research found that one-third of the world’s 100 largest cities draw a substantial proportion of their drinking water from forest protected areas (Dudley and Stolton 2003). Similarly, forests and other vegetation types can absorb a certain amount of air pollution and provide valuable shading. The ability of an ecosystem to neutralise pollutants is significant and important, but by no means infinite, and high pollution levels are also a major threat to some protected areas, most dramatically in the case of ocean acidification due to rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. Wetland protected areas also provide valuable water storage services, and protection of buffer zones around lakes and rivers helps to prevent pollution. - Pollination

Apart from its critical role in maintaining species diversity and vegetation patterns, pollination has direct utilitarian roles for humans, as an essential part of agriculture and fruit growing, and as a stimulant for the production of honey. In a world where pesticides, industrial pollution and habitat loss have had a catastrophic impact on insect numbers, protected areas are increasingly being seen as a tool for maintaining pollination services. Many protected areas allow local beekeepers to place beehives with native bee species within the protected area. Farmers benefit from pollination services maintained within the protected area itself and spilling out into farmland and orchards, and protected area planners are starting to realise that they need to include the retention and where necessary restoration of pollination pathways within conservation planning exercises. - Pest and disease regulation

Controlling serious pests and diseases is increasingly important as the degree of threat from invasive alien species is recognised and climate change encourages the spread of pests and diseases into new ecosystems. Protected areas can help minimise these problems in a number of ways, particularly by physically blocking unwanted species: many invasive plants are coloniser species and do not penetrate into mature vegetation. The same is true of some insect pests like the tsetse fly, and malarial mosquitoes have also been recorded as moving far more slowly through dense forests. - Cultural services - Clearly not all the benefits we derive from natural ecosystems are narrowly utilitarian: humans enjoy a wealth of complicated cultural, psychological and spiritual links with the natural world. Because protected areas tend to be established in particularly beautiful and pristine parts of nature, these cultural services are particularly strongly represented.

- Recreation and tourism

The day-to-day uses of nature for relaxation, exercise and psychological renewal stretch back way beyond recorded history and have been a major driver for protected area creation. Most visitors tend to cluster around the edges of large reserves and keep to footpaths—for walks, family outings, picnics and nature watching; a smaller subset of visitors likes to penetrate much deeper, walking, riding or canoeing for days inside the larger national parks. For these people, the sense of isolation and wilderness is a key part of the attraction. With tourism now arguably the world’s largest single industry, the potential for ecotourism in protected areas is growing all the time and is already the largest foreign currency earner in countries such as Tanzania. - (Nature-based) physical and mental

wellbeing

As well as the benefits from recreational use of protected areas, research and practice have found that people with physical and mental problems or alcohol and other drug addictions can benefit positively from immersion in an attractive landscape. Health authorities in the United Kingdom are encouraging use of local nature reserves as safe and appealing places for exercise, to combat a national obesity problem. The ‘Healthy Parks Healthy People’ movement, started in Melbourne, Australia, links protected area and health agencies and uses parks to provide relaxing places for people with mental health issues and/or substance addiction. These approaches have proved very encouraging and a pleasant environment has proven to be good psychological and physical therapy. - Aesthetic value and a sense of place

and inspiration for arts, science and

technology

Perceptions of beauty are culturally formed. The Romantic movement in the arts was a major stimulus for the development of national parks in Europe (Box 6.3). Iconic national parks like Yellowstone in the United States, the Blue Mountains outside Sydney, Australia, the Lake District in the United Kingdom and the Japanese Alps have inspired artists and writers for generations, and on a more local scale protected areas provide rich sources of ideas and energy for poets, painters, musicians and other artists. A ‘sense of place’ is also a useful concept for describing and understanding the attachments some people form with protected areas (Lin and Lockwood 2013). Such place attachments can include emotional (including identity) and functional aspects even for communities who have only recent connections with a protected area. - Education and research

Protected areas provide an ideal location for ecological research as they are often in fairly pristine condition, and have sympathetic staff and sometimes facilities for visiting scientists. A proportion of reserves are set up specifically for research purposes, and these are amongst the most strictly protected areas in terms of access and disturbance, so ecological processes and interactions can be studied under the best possible circumstances. Other protected areas have extensive education programs, often developed in association with local schools and colleges, giving children an increasingly rare opportunity to interact directly with nature. - Spiritual and religious experience

Many protected areas contain sites of spiritual importance (see Chapters 4 and 23). Protected areas can, if sensitively managed, accommodate such interests, and can provide both additional protection and a pleasant surrounding environment for meditation and worship. In Amber Mountain National Park, northern Madagascar, local people can visit a sacred waterfall within the park, and in Donaña National Park in southern Spain every year a major pilgrimage takes place, linked to the Catholic Church. To an increasing extent, resident faith groups within protected areas are becoming actively involved in conservation, as in Rila National Park in Bulgaria, where the monks in Rila Monastery manage their own lands as a nature reserve, in accordance with teachings about the sanctity of nature. - Cultural identity and heritage

The cultural and historical values found within protected areas are also often very important although sometimes rather difficult to define. In the same way that iconic buildings, writers, musicians and football teams can come to embody the heart of a nation or region, so too can special views, landscapes or wild species. Climbing Mount Triglav, in the national park of the same name, is something many Slovenians intend to do at least once in their life. Further east in Europe, Mount Kazbegi has a potent mixture of cultural and spiritual values for many Georgians, who visit the ancient church built high in the mountains under its shadow. - Peace and stability

Many conflicts between nation-states focus on the borders between countries. The first trans-boundary conservation initiative in the modern sense of the term is attributed to the Waterton–Glacier International Peace Park, which was declared in 1932 to commemorate the peace and goodwill that exist along the world’s longest undefended border, between Canada and the United States. Several other trans-boundary protected areas have been effective in helping resolve boundary disputes between countries. For example, the establishment of protected areas in the Carpathian Mountains in Central and Eastern Europe between 1949 and 1967 helped settle boundary disputes, and the Cordillera del Cóndor Transboundary Protected Area along a portion of the border between Ecuador and Peru was declared as part of the resolution of a boundary dispute between the two countries.

Challenges

How to manage areas protected for conservation brings up a range of challenges - whether it be regarding the local population, specific ecosystems or the design of the reserve itself - and because of the many unpredicatable elements in ecology issues, each protected area requires a case-specific set of guidelines. Enforcing protected area boundaries is a costly and labour-heavy endeavour, particularly if the allocation of a new protected region places new restrictions on the use of resources by the native people which may lead to their subsequent displacement. This has troubled relationships between conservationists and rural communities in many protected regions and is often why many Wildlife Reserves and National Parks face the human threat of poaching for the illegal bushmeat or trophy trades, which are resorted to as an alternative form of substinence. There is increasing pressure to take proper account of human needs when setting up protected areas and these sometimes have to be "traded off" against conservation needs. Whereas in the past governments often made decisions about protected areas and informed local people afterwards, today the emphasis is shifting towards greater discussions with stakeholders and joint decisions about how such lands should be set aside and managed. Such negotiations are never easy but usually produce stronger and longer-lasting results for both conservation and people. In some countries, protected areas can be assigned without the infrastructure and networking needed to substitute consumable resources and subtantiatively protect the area from development or misuse. The soliciting of protected areas may require regulation to the level of meeting demands for food, feed, livestock and fuel, and the legal enforcement of not only the protected area itself but also 'buffer zones' surrounding it, which may help to resist destabilisation.

Protected Area Categories

IUCN protected area management categories classify protected areas according to their management objectives. The categories are recognised by international bodies such as the United Nations and by many national governments as the global standard for defining and recording protected areas and as such are increasingly being incorporated into government legislation.

Category Ia: Strict Nature Reserve

Protected areas that are strictly set aside to protect biodiversity and also possibly geological/geomorphological features, where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values. Such protected areas can serve as indispensable reference areas for scientific research and monitoring.

Category Ib: Wilderness Area

Protected areas that are usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.

Category II: National Park

Large natural or near natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities.

Category III:Natural Monument or Feature

Protected areas set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, sea mount, submarine cavern, geological feature such as a cave or even a living feature such as an ancient grove. They are generally quite small protected areas and often have high visitor value.

Category IV: Habitat/Species Management Area

Protected areas aiming to protect particular species or habitats and management reflects this priority. Many category IV protected areas will need regular, active interventions to address the requirements of particular species or to maintain habitats, but this is not a requirement of the category.

Category V: Protected Landscape/Seascape

A protected area where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character with significant ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value: and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values.

Category VI: Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources

Protected areas that conserve ecosystems and habitats, together with associated cultural values and traditional natural resource management systems. They are generally large, with most of the area in a natural condition, where a proportion is under sustainable natural resource management and where low-level non-industrial use of natural resources compatible with nature conservation is seen as one of the main aims of the area.

Conservation Areas in Ontario

Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area

Located southwest of Milton on the Niagara Peninsula, Rattlesnake Point offers sweeping views of the bucolic landscape below the gorge heading down to Lake Ontario. Trails line the top of the escarpment, which regularly open to sweeping vistas of farmland and the azure lake. Cyclists will want to test their mettle of the climb up Appleby Road leading into the park. It's one of the toughest in Ontario.

Limehouse Conservation Area

Limehouse Conservation Area is part of the CVC and the Bruce Trail runs through it. This conservation area has beautiful trails, amazing views of the Credit River, restored limestone kilns and ruins and the geological heart of the area known as the “Hole in the Wall.”

There are 5 trails in total, including Kiln Trail 0.05 km, CVC Trail 0.9 km, the Black Creek Side Trail 1.5 km and the Bruce Trail 1.9 km along which the Stone Bridge, Mill Ruins, Lime Kilns and Powder House can be found. The trails are arranged in loops allowing you to hike the entire area not having to back track and experience new views at every turn. We hiked 5.99 km.

Belfountain Conservation Area

Located beside the Forks of the Credit Provincial Park, Belfountain might be the prettiest conservation area near Toronto. The river and its many small waterfalls is much nicer than the streams we tend to find at the bottom of our ravines, and the woods are absolutely spectacular with saturated colour come mid-October. Hit the swing bridge over the river for a great view and a bit of adventure. There's also numerous trails and picnic facilities.

Websites About Protected Areas

- International Union for Conservation of Nature

- Ontario Nature Blog

- Protected Planet

- Marine Protection Atlas

- Conservation Corridor

- Large Landscape Conservation

References

- Logo by: Gerome Dulalas

- Valuing Protected Areas Book by World Bank GEF Operations

- Values and Benefits of Protected Areas by Sue Stolton and Nigel Dudley

Back to index